OVARIAN EGG MORPHOLOGY IN CHALCIDOID WASPS (HYMENOPTERA: CHALCIDOIDEA) PARASITIZING GALL WASPS (HYMENOPTERA: CYNIPIDAE)

H. Vårdal1, J. F. Gómez2 & J. L. Nieves-Aldrey3

1Swedish Museum of Natural History, Department of Zoology, Box 50007, SE-1004 05 Stockholm, Sweden. e-mail: hege.vardal@nrm.se

2Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas, Departamento de Zoología y Antropología Física, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Jose Antonio Novais, 2. E-28040 Madrid, Spain. e-mail: jf.gomez@bio.ucm.es

3Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, Departamento de Biodiversidad y Biología Evolutiva, José Gutiérrez, Abascal 2, 28006 Madrid, Spain. e-mail: aldrey@mncn.csic.es (corresponding author)

| |

ABSTRACT

We provide morphological egg data of 26 species of 5 chalcidoid families associated with cynipid galls (Hymenoptera: Cynipidae)

from western Palaearctic, including the first egg data for the family Ormyridae. Adult chalcidoid species were reared from

galls, and eggs obtained from dissected female ovaries were examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The shape of

the eggs varies from oval to elongate and tapered at both ends. Eggs of Eurytomidae as well as some Eulophidae, Eupelmidae

and Pteromalidae are equipped with a peduncle at the anterior end. We found a positive correlation between long eggs and long

ovipositors and confirmed the expectation that eggs of endoparasitoids are generally shorter and narrower than eggs of ectoparasitoids.

We were able to locate the sperm entrance or micropyle at the anterior pole of eggs of several species. It is situated at

the anterior end of the egg and at the end of the peduncle when present. In addition, the eggshells of the endoparasitoid

Sycophila biguttata (Swederus, 1795) (Hymenoptera: Eurytomidae) and the ectoparasitoid Cecidostiba fungosa (Geoffroy, 1785) (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae), are for the first time described.

Key words: chalcidoid egg ultrastructure;

micropyle;

eggshell;

mode of parasitism;

immature stages.

|

| |

RESUMEN

Morfología del huevo ovárico en calcidoideos (Hymenoptera: Chalcidoidea) parasitoides de avispas de las agallas (Hymenoptera:

Cynipidae)

En el presente trabajo se aportan datos morfológicos del huevo de 26 especies del Paleártico occidental pertenecientes a 5

familias de Chalcidoidea asociadas con agallas de cinípidos (Hymenoptera: Cynipidae), incluyendo los primeros datos del huevo

de especies de Ormyridae. Los ejemplares adultos de las especies estudiadas fueron obtenidos por emergencia de agallas en

laboratorio, los ovarios de las hembras diseccionados para obtener los huevos, que fueron finalmente estudiados utilizando

técnicas de microscopía electronica de barrido. La forma de los huevos estudiados varía de ovalada a alargada y ahusada en

ambos extremos. Los huevos de Eurytomidae, así como algunos de Eulophidae, Eupelmidae y Pteromalidae están provistos de un

pedúnculo en el extremo anterior. Se encontró una correlación positiva entre aquellos huevos elongados y la presencia de ovipositores

largos en las hembras, confirmándose también la hipótesis esperada de que los huevos de especies endoparasitoides son generalmente

más cortos y estrechos que los de los ectoparasitoides. Por otro lado los estudios de ultraestructura en los huevos de varias

especies han permitido la localización del punto de entrada de esperma o micropilo. Este se encuentra situado bien en el extremo

anterior del huevo o bien en el extremo del pedúnculo cuando está presente. Además, por primera vez se estudia y se describe

la ultraestructura de la cáscara del huevo de la especie endoparasitoide Sycophila biguttata (Swederus, 1795) (Hymenoptera: Eurytomidae) y del ectoparasitoide Cecidostiba fungosa (Geoffroy, 1785) (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae).

Palabras clave: ultraestructura del huevo de chalcidoidea;

micropilo;

cáscara de huevo;

modo de parasitismo;

estados inmaduros.

|

IntroductionTOP

The most diverse group of parasitic wasps is probably the superfamily Chalcidoidea (Hymenoptera) with its 22000 described

species and an immense variety of life modes (Noyes, 1978, 1990a; Gordh et al., 1979; Gibson, 1993). Most chalcidoids are entomophagous and attack 339 arthropod families (Clausen, 1940; Noyes, 2002). The great majority are egg and larval parasitoids, while some groups are, at least in part, phytophagous gall inhabitants on as much 444 plant families (Noyes, 2002) or even true gall inducers (La Salle, 2005).

The gall wasps or cynipids (Hymenoptera: Cynipidae) is a large group of Hymenoptera representing one of the more speciose

radiations of gall-inducing insects with more than 1400 species described (Nieves-Aldrey, 2001). The classification of the family has been recently revised into twelve tribes which are strongly supported as monophyletic

(Ronquist et al., 2015), nine of which are represented in the western Palaeartic. In addition of their intrinsic biological interest, plant galls

induced by Cynipidae host large communities of insects which are composed mainly of other cynipid inquiline species and parasitoids

which attack all the gall inhabitants. These micro communities support intrincate food webs which have been focus of many

ecological studies (Askew, 1961; Schönrogge et al., 1995, 1996; Bailey et al., 2009).

The parasitoids inhabitant cynipid galls in western Palaearctic belong mainly to six chalcidoid families: Euytomidae, Torymidae,

Ormyridae, Pteromalidae, Eupelmidae and Eulophidae. This parasitoid fauna has been catalogued in recent years (Askew et al., 2006, 2013).

Egg and eggshell can be useful for identification of chalcidoid species (Askew, 1961). For instance Claridge & Askew (1960) showed clear differences in the egg between species of Eurytoma rosae Nees, 1834 species-group. Extensive morphological variability in egg structure has been observed between and within families of Chalcidoidea. The egg is short and oval or slender and elongate (Parker, 1924a; Clausen, 1940; Iwata, 1962). A summary of external features of the chalcidoid egg from literature is given in Table 1.

Table 1.— Chalcidoid egg data summarized from literature.

Tabla 1.— Datos de los huevos de Chalcidoidea tomados de la bibliografía.

| Family |

Egg shape |

Ovarian or post-oviposition egg observed |

Egg surface |

Anterior peduncle |

Posterior process |

References |

| Agaonidae |

dumb-bell shaped (ovarian), elongate (post-ovarian) |

Ovarian & post-oviposition |

smooth |

present |

absent |

Grandi (1929)

|

| Aphelinidae |

elongate, curved, wider at anterior end |

Ovarian & post-oviposition |

smooth, translucent |

present or absent |

absent |

Compere & Smith (1932), Cendaña (1937), Parker (1924a)

|

| Chalcididae |

elongate, curved and wider at anterior end |

Post-ovipostion |

smooth, some sculpture around micropyle |

present or absent |

absent |

Parker (1924b), Dowden (1935)

|

| Encyrtidae |

dumb-bell shaped (encyrtiform), or elongate |

Ovarian & post-oviposition |

may be partly sculptured |

present |

absent |

Clancy (1946), Hagen (1964), Noyes (1990b)

|

| Eucharitidae |

Oval or curved dorsally and flattened ventrally |

Ovarian & post-oviposition |

smooth |

present |

absent |

Parker (1924a), Heraty & Darling (1984)

|

| Eulophidae |

elongate, curved, broader at anterior end |

Ovarian & post-oviposition |

smooth |

present or absent |

absent |

Parker (1924a), Cameron (1939), Clancy (1946)

|

| Eupelmidae |

Elongate |

Ovarian & post-oviposition |

smooth |

present |

present |

Phillips & Poos (1921), Clancy (1946)

|

| Eurytomidae |

Elongate |

Ovarian & post-oviposition |

smooth, some with spines or lattice-structure |

present |

present |

Claridge & Askew (1960), Arthur, (1961), Fisher (1965)

|

| Leucospidae |

elongate, curved, wider at anterior end |

Ovarian & post-oviposition |

tubercles, sharply pointed at anterior end, rounded at posterior end |

present |

absent |

Fabré (1886), Parker (1924a)

|

| Mymaridae |

elongate |

Ovarian & post-oviposition |

|

present |

absent |

Clausen (1940), Jackson (1961)

|

| Perilampidae |

elongate, slightly flatterned ventrally, tapering at anterior end |

Ovarian & post-oviposition |

heavily sculptured |

Absent |

absent |

Heraty & Darling (1984), Smith (1917), Parker (1924a)

|

| Pteromalidae |

elongate, tapering towards both ends |

Ovarian & post-oviposition |

smooth or covered with papillae |

Most often absent, but present in some |

absent |

Parker (1924a), Cameron (1939), Clancy (1946)

|

| Tanaostigmatidae |

may be dumb-bell shaped |

Ovarian & post-oviposition |

unknown |

present |

absent |

La Salle & LeBeck (1983)

|

| Torymidae |

elongate, tapering toward both ends |

Ovarian & post-oviposition |

smooth or covered with spines |

Most often absent, but present in some |

absent |

Parker (1924a), Muesebeck (1931), Askew (1961), Askew (1966), Phillips & Poos (1921)

|

| Trichogrammatidae |

ellipsoid or elongate, strongly tapering at posterior end |

Ovarian & post-oviposition |

smooth or partly heavily sculptured |

present or absent |

absent |

Silvestri (1916), Bakkendorf (1934), Parker (1924a)

|

| Signiphoridae |

banana-shaped |

Post-ovipostion |

unknown |

present |

absent |

Rosen et al. (1992)

|

The eggshell ultrastructure has been described for a handful of chalcidoids including Nasonia vitripennis (Walker, 1836) (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae) (King et al., 1968; Richards, 1969) and Eurytoma amygdali Enderlein, 1907 (Hymenoptera: Eurytomidae) (Mouzaki & Margaritis, 1994; Zarani & Margaritis, 1994). It typically consists of a thin vitelline membrane, adjacent and often attached by interlocking ridges to the oocyte (King et al., 1968) and an outer chorion. The chorion is divided into an inner electron-translucent endochorion and an outer electron-dense exochorion (King et al., 1968; Richards, 1969; Mouzaki & Margaritis, 1994). The endochorion has a uniform smooth structure, whereas the exochorion may have sublayers of granular and columnar structure

(Mouzaki & Margaritis, 1994). Spines originating from the endochorion and extending through the exochorion and onto the egg surface were found in Catolaccus (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae) (King et al., 1968). The structure and elasticity of the eggshell facilitate the stretching of the egg through the narrow and long ovipositor.

Thus the chorion appears to be reduced in structure, i.e. fewer layers, compared with insects with different oviposition requirements

(i.e. diameter of the ovipositor relative to egg width) like the reduviid Rhodnius prolixus Stahl that has seven layers in its chorion (Beament, 1946; King et al., 1968; Richards, 1969). The endochorion has been shown to contain peroxidase in Eurytoma amygdali (Hymenoptera: Eurytomidae) to provide elasticity (Mouzaki & Margaritis, 1994; Zarani & Margaritis, 1994). The anterior micropylar region of the egg of Nasonia vitripennis (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae) is marked by an opening or by several grooves (King, 1962) on the external surface of the chorion. In Eurytoma amygdali (Hymenoptera: Eurytomidae), it is situated at the end of a short posterior filament, the micropylar appendage in the posterior

end of the egg (Zarani & Margaritis, 1994). The structure of the eggshell often reflects mode of parasitism. Endoparasitic species often have a thin hydropic eggshell

that can take up nutrients from the surrounding host tissue (Margaritis, 1985).

The aim of the study was to provide new data on the egg morphology of chalcidoids by analysing species associated with cynipid

galls. Descriptive data on immature stages of species inhabitant cynipid galls are potentially important for studies such

as phylogenetic analyses, the ecology of chalcidoid communities, as well as studies of food webs. In recent years some works

have been published on comparative morphology of terminal-instar larvae of species of several chalcidoid families associated

to gall wasps in Europe (Nieves-Aldrey et al., 2008; Gómez et al., 2008, 2011, 2013; Gómez & Nieves-Aldrey, 2012). However there are not similar comprehensive studies on egg morphology of the same or related species. We give here scanning

electron micrographs showing the eggs of 3 species of Eulophidae, 1 Eupelmidae, 8 Eurytomidae, 3 Ormyridae, 4 Pteromalidae

and 7 Torymidae as well as transmission electron micrographs showing the eggshell ultrastructure of 1 Eurytomidae (Sycophila biguttata) and 1 Pteromalidae (Cecidostiba fungosa). Data on egg shape variation, as well as aspects of egg and eggshell properties and oviposition habits are also investigated.

Furthermore the ultrastructure of the eggshells of these species is described for the first time. Finally the micropyle and

eggshell surface structure are shown for a number of the species.

Material and methodsTOP

SELECTED TAXA

We studied the eggs of 26 species of Chalcidoidea collected in Spain and Sweden between 2000 and 2007 (Table 2). The females were reared from cynipid galls on Asteraceae, Fagaceae, Lamiaceae, Papaveraceae, Rosaceae and Sapindaceae induced

by species of the tribes Aylacini, Aulacideini, Diastrophini, Diplolepidini, Pediaspidini and Cynipini (Table 2). Taxonomy of cynipids follows Nieves-Aldrey (2001) and Ronquist et al. (2015).

Table 2.— Taxonomy, hosts and material used in the present study. A = asexual generation, S = sexual generation, − = no alternate generation. The eggshell ultrastructure was examined for the species marked * and post-oviposition egg were observed for species marked #.

Tabla 2.— Taxonomía hospedadores y materiales utilizados en el presente estudio. A = generación asexual, S = generación sexual, − = sin generación alternante. La ultraestructura de la cascara del huevo fue examinada para las especies marcadas * y el huevo después de la puesta fue observado para las especies con el símbolo #.

| Studied Chalcidoidea species |

Family |

Gall wasp inducer host (generation) |

Host plant |

Chalcidoid life mode |

Collecting sites |

| Aprostocetus epicharmus |

Eulophidae |

Aylax minor |

Papaver dubium. |

endoparasitoid |

Spain, Madrid, Rivas-Vaciamadrid. 20/VI/99; VI/99 J. L. Nieves leg. |

| Aulogymnus skianeuros |

Eulophidae |

Biorhiza pallida (S)

|

Quercus faginea |

ectoparasitoid |

Spain, Toledo, Robledo del Mazo 11/III/06 J.L. Nieves leg. |

| Dichatomus acerinus |

Eulophidae |

Pediaspis aceris (S)

|

Acer opalus |

inquiline |

Spain, Tarragona, Colldejou. 14/VIII/03; 1-7/III/04. J. L. Nieves leg |

| Eupelmus microzonus |

Eupelmidae |

Isocolus lichtensteini (-)

|

Centaurea melitensis |

ectoparasitoid |

Spain, Madrid, Dehesa de Arganda. 12/II/04; 15-21/III/04. J. L. Nieves leg. |

| Eurytoma brunniventris# |

Eurytomidae |

Trigonaspis synaspis (A)

|

Quercus pyrenaica |

ectoparasitoid |

Spain, Madrid, Miraflores 3/IX/05. J. L. Nieves leg. |

| Eurytoma infracta |

Eurytomidae |

Neaylax verbenacus (-)

|

Salvia verbenaca |

ectoparasitoid |

Spain, Madrid, Dehesa de Arganda 6/VI/99; VIII/99. J. L. Nieves leg. |

| Eurytoma rosae# |

Eurytomidae |

Diplolepis rosae (-)

|

Rosa sp.

|

ectoparasitoid |

Spain, Madrid, Nuevo Baztán 23/04/05. J. L. Nieves leg. |

| Eurytoma strigifrons |

Eurytomidae |

Isocolus lichtensteini (-)

|

Centaurea melitensis |

ectoparasitoid |

Spain, Madrid, Dehesa de Arganda. 12/II/04; 15-21/III/04. J. L. Nieves leg. |

| Sycophila biguttata* |

Eurytomidae |

Biorhiza pallida (S)

|

Quercus faginea |

endoparasitoid |

Sweden, Uppland, Stockholm, Ekhagen, 16/VII/07, H. Vårdal, leg. |

| Sycophila binotata |

Eurytomidae |

Plagiotrochus quercusilicis (A)

|

Quercus ilex |

endoparasitoid |

Spain, Granada, Vivero Egmasa 17/I/06; IV/06. J. L. Nieves leg. |

| Sycophila mayri |

Eurytomidae |

Phanacis centaureae |

Centaurea sp.

|

endoparasitoid |

Spain, Madrid, Dehesa de Arganda. 21/IV/05. J. L. Nieves leg |

| Sycophila submutica |

Eurytomidae |

Isocolus lichtensteini (-)

|

Centaurea melitensis |

endoparasitoid |

Spain, Madrid, Dehesa de Arganda. 12/II/04; 23-29/II/04. J. L. Nieves leg. |

| Ormyrus nitidulus |

Ormyridae |

Andricus hispanicus (A)

|

Quercus canariensis |

ectoparasitoid |

Spain, Madrid, Algatocín. 19/VIII/02. J. L. Nieves leg. |

| Ormyrus papaveris |

Ormyridae |

Aylax minor (-)

|

Papaver rhoeas |

ectoparasitoid |

Spain, Madrid, Rivas-Vaciamadrid. 20/VI/99; VI/99 J. L. Nieves leg. |

| Ormyrus wachtli |

Ormyridae |

Neaylax verbenacus (-)

|

Salvia verbenaca |

ectoparasitoid |

Spain, Madrid, Dehesa de Arganda. 1/VI/03; VI/03 J. L. Nieves leg. |

| Cecidostiba fungosa* |

Pteromalidae |

Biorhiza pallida (S)

|

Quercus robur |

ectoparasitoid? |

Spain, Madrid, Chapinería.15/V/00. J. L. Nieves leg. |

| Mesopolobus mediterraneus |

Pteromalidae |

Biorhiza pallida (S)

|

Quercus faginea |

ectoparasitoid? |

Spain, Madrid, Chapinería.15/V/00. J. L. Nieves leg. |

| Pteromalus bedeguaris# |

Pteromalidae |

Diplolepis rosae (-)

|

Rosa spp.

|

ectoparasitoid? |

Spain, Madrid, Borox. 7/III/03. J. L. Nieves leg. |

| Stinoplus lapsanae |

Pteromalidae |

Timaspis lampsanae (-)

|

Lampsana communis |

ectoparasitoid? |

Spain, Madrid, El Escorial, 06/XII/84, J.L. Nieves leg. |

| Adontomerus impolitus |

Torymidae |

Aulacidea tragopogonis (-)

|

Tragopogon spp

|

ectoparasitoid |

Spain, Madrid, El Campillo-Rivas. 6/III/05; V/05. J. L. Nieves leg. |

| Chalcimerus borceai |

Torymidae |

Barbotinia oraniensis |

Papaver rhoeas |

ectoparasitoid |

Spain, Madrid, El Campillo-Rivas. 22/II/04; 18/IV/04. J. L. Nieves leg. |

| Glyphomerus stigma |

Torymidae |

Diplolepis mayri |

Rosa sp.

|

ectoparasitoid |

Spain, Ourense, Rubiá, 16/VI/03, J.L. Nieves leg |

| Megastigmus aculeatus |

Torymidae |

- |

Rosa sp.

|

seed eater |

Spain, Segovia, Siguero 1/V/07. J. L. Nieves leg. |

| Torymus bedeguaris* |

Torymidae |

Diplolepis rosae |

Rosa spp.

|

ectoparasitoid |

Sweden, Öland, 3/V/2007. H. Vårdal leg. |

| Torymus nobilis |

Torymidae |

Biorhiza pallida (A)

|

Quercus pyrenaica |

gregarious ectoparasitoid |

Spain, Madrid, Miraflores. 10/XII/02; VI,03. J.L. Nieves leg. |

| Torymus rubi |

Torymidae |

Diastrophus rubi (-)

|

Rubus spp.

|

ectoparasitoid |

Spain, Asturias, Ajuyán-Oviedo. 7/IX/05; X/05. L. Parra leg. 2♀♀ |

REARING AND DISSECTION

Adult females were reared from galls stored in rearing cages or extracted after dissection of galls. Eggs were dissected from

the ovaries of the females and counted. It is often difficult to count the number of eggs in the ovaries as the egg may be

covered with ovarian sheets and be in varying degree of maturity, thus the egg count given in Table 4 for each species is approximate. Potential difficulties by using only ovarian eggs for descriptions may be that in some species

the eggs tend to transform dramatically after oviposition, and sometimes ovarian tissue may conceal the surface structure

of each individual egg (HV, personal observation). In the present study only ovarian eggs have been observed with the exception

of the very few cases when we happened to find deposited eggs inside galls (see Table 2, Fig. 11). The most mature eggs in the ovaries were selected for the study. We leave the study of post-oviposition eggs for later

studies.

PREPARATIONS FOR MORPHOLOGICAL STUDIES

Prior to scanning electron microscopy the adult females were preserved in absolute alcohol and ovarian eggs were dissected

and put directly on SEM stubs and into the scanning electron microscope (Zeiss Supra35VP and FEI Quanta 200) on low vacuum without critical point drying or gold coating.

For transmission electron microscopy, the reared females were fixed in PAGF (Stefanini et al., 1967) for 1-2 months. Eggs were dissected and fixed in osmium-tetroxide and dehydrated through an ethanol series, finishing with

acetone. The specimens were then infiltrated with 1:1 solution of acetone and epoxy resin (Epon 812) over night and then in

pure resin at 60 degrees Celsius for 48 hours before sectioning (60 nm thin sections on copper grids), triple-dyeing in lead

citrate- uranyl acetate-lead citrate, and examination in an LEO 912 AB transmission electron microscope.

TERMINOLOGY AND MEASUREMENTS

General terminology used in egg and eggshell descriptions follows King (1962) and Margaritis (1985).

The length of the egg body is measured from the posterior tip to the transition between the egg body and the peduncle (Table 3). The width measurement is taken at the maximum width of the egg body. Only external measurements of the ovipositor were

taken. The length of the ovipositor was measured from the side. The ovipositor width was measured from the ventral side at

the narrowest point at the apical tip and at the broadest point at the basal articulation (Table 3).

Table 3.— Egg and ovipositor measurements. Ranges are given for the species for which less than 4 specimens were measured, whereas mean and standard deviations are given when n≥4. The ovipositor width was measured at apical point and at base. All measurements are given in μm.

Tabla 3.— Medidas del huevo y del ovipositor. Se dan los intervalos para los cuales se midieron menos de 4 ejemplares, mientras que la media y la desviación estándar se dan cuando n≥4n. La anchura del ovipositor se midió desde el extremo apical al basal. Todas las medidas se dan en μm.

| Studied Chalcidoidea species (families) |

Egg body length |

Peduncle length |

Egg body width |

Posterior process length |

Ovipositor external length |

Ovipositor external width |

| Aprostocetus epicharmus |

135-175 (n=2) |

no peduncle |

30-45 (n=2) |

no process |

770 (n=1) |

10-15 (n=1) |

| Aulogymnus skianeuros |

150-160 (n=3) |

140-160 (n=3) |

48-65 (n=3) |

no process |

1275 (n=1) |

15-35 (n=1) |

| Dichatomus acerinus |

113.2±6.8 (n=5) |

no peduncle |

42±5,7 (n=5) |

no process |

775 (n=1) |

20-35 (n=1) |

| Eupelmus microzonus |

268.8±10.3 (n=4) |

323.8±19.7 (n=4) |

77.5±2.9 (n=4) |

30-35 (n=2) |

2125 (n=1) |

20-60 (n=1) |

| Eurytoma brunniventris |

200-220 (n=2) |

290-310 (n=2) |

60-70 (n=2) |

35 (n=1) |

1075-1750 (n=2) |

20-60 (n=2) |

| Eurytoma infracta |

250-320 (n=2) |

380 (n=1) |

60-70 (n=2) |

20-35 (n=2) |

1200-1375 (n=2) |

10-40 (n=2) |

| Eurytoma rosae |

360 (n=1) |

300 (n=1) |

90 (n=1) |

no process |

2275 (n=1) |

20-70 (n=1) |

| Eurytoma strigifrons |

254±11.4 (n=5) |

435±44.7 (n=5) |

82±7.6 (n=5) |

50±3.5 (n=5) |

2475 (n=1) |

20-60 (n=1) |

| Sycophila biguttata |

115±5 (n=5) |

always broken (1 at least 200) |

57±4,5 (n=5) |

20 (n=1) |

2325-2625 (n=2) |

10-60 (n=2) |

| Sycophila binotata |

148,8±8,5 (n=4) |

always incomplete (1 at least 550) |

46,3±4,8 (n=4) |

22,5±2,9 (n=4) |

1875 (n=1) |

15-40 (n=1) |

| Sycophila mayri |

150 (n=2) |

always incomplete (1 at least 600) |

30-45 (n=2) |

not visible or flat to egg |

1975 (n=1) |

10-35 (n=1) |

| Sycophila submutica |

95-130 (n=3) |

always incomplete (1 at least 260) |

35-55 (n=3) |

20-30 (n=3) |

ovipositor broken at base, missing |

at ovipositor base: 50 |

| Ormyrus nitidulus |

760-810 (n=3) |

no peduncle |

80-120 (n=3) |

no process |

5100-5250 (n=2) |

20-50 (n=2) |

| Ormyrus papaveris |

384±83,2 (n=5) |

no peduncle |

70±15,8 (n=5) |

no process |

2075-3125 (n=2) |

15-60 (n=2) |

| Ormyrus wachtli |

333±32,1 (n=5) |

no peduncle |

80±7,1 (n=5) |

no process |

1350 (n=1) |

15-50 (n=1) |

| Cecidostiba fungosa |

250 (n=1) |

no peduncle |

50 (n=1) |

no process |

2025 (n=1) |

20-45 (n=1) |

| Mesopolobus mediterraneus |

85 (n=1) |

no peduncle |

50 (n=1) |

no process |

1250 (n=1) |

15-35 (n=1) |

| Pteromalus bedeguaris |

390-520 (n=3) |

no peduncle |

40-90 (n=3) |

no process |

2200 (n=1) |

15-70 (n=1) |

| Stinoplus lapsanae |

290 (n=1) |

no peduncle |

60 (n=1) |

no process |

1550 (n=1) |

10-30 (n=1) |

| Adontomerus impolitus |

405-420 (n=2) |

no peduncle |

60 (n=2) |

no process |

2450 (n=1) |

15-40 (n=1) |

| Chalcimerus borceai |

460 (n=1) |

no peduncle |

65 (n=1) |

no process |

3425 (n=1) |

15-90 (n=1) |

| Glyphomerus stigma |

660 (n=1) |

no peduncle |

75 (n=1) |

np process |

1425-5100 (n=3) |

15-120 (n=3) |

| Megastigmus aculeatus |

125-140 (n=2) |

480-680 (n=2) |

45-60 (n=2) |

20 (n=2) |

4100-5225 (n=2) |

15-70 (n=2) |

| Torymus nobilis |

497,5±37,8 (n=4) |

no peduncle |

76,3±10,3 (n=4) |

no process |

4400 (n=1) |

20-80 (n=1) |

| Torymus rubi |

53-70 (n=2) |

no peduncle |

32-40 (n=2) |

no process |

3825 (n=1) |

15-80 (n=1) |

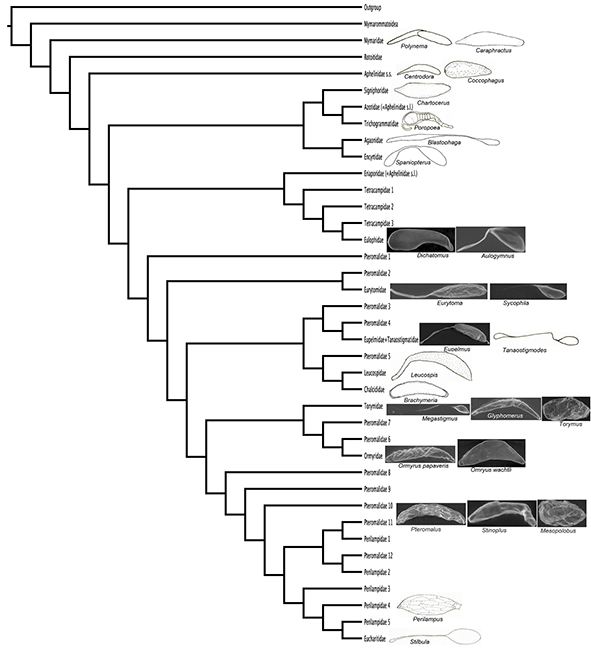

To examine how the egg shape varies within the Chalcidoidea, the different egg shapes were drawn onto a recent phylogeny (Fig. 12) (Heraty et al., 2013). Redrawings from previous authors’ illustrations were included (Silvestri, 1916; Parker, 1924a; Grandi, 1929; Dowden, 1935; Cendaña, 1937; Clausen, 1940; Jackson, 1961; La Salle & LeBeck 1983; Noyes, 1990a; Rosen et al., 1992).

ResultsTOP

Egg and ovipositor measurements are given in Table 3 and egg shape characters, approximate egg counts as well as environment at egg deposition site are given in Table 4.

Pedunculate eggs were observed in 5 families (Figs. 1-3, 5-6; Table 4) and non-pedunculate egg in Eulophidae (Fig. 1), Ormyridae (Fig. 4), Pteromalidae (Fig. 5) and Torymidae (Fig. 6).

Table 4.— Egg characters, counts and oviposition environment. Short peduncle length = less or equal to 340 μm, Long peduncle length = longer than 340 μm. Egg body length: Short: 250 μm or less, Long: longer than 250 μm. Ovipositor length: Short: 2162 μm or shorter, Long: longer than 2162 μm.

Tabla 4.— Caracteres del huevo, conteos y datos ambientales del ovipositor. Longitud del pedúnculo corto=menor o igual a 340 μm, longitud del pedúndulo largo = más largo que 340 μm. Longitud del cuerpo del huevo: Corto: 250 μm o menos, Largo: más largo que 250 μm. Longitud del ovipositor: Corto: 2162 μm o más corto, Largo: más largo que 2162 μm.

| Species |

Egg shape |

Egg surface |

Anterior peduncle |

Posterior process |

Egg count (approx) |

Ovipositor |

Oviposition substrate/environment |

| Aprostocetus epicharmus |

Pear, short |

smooth |

Absent |

absent |

- |

short |

inside larva, fluid |

| Aulogymnus skianeuros |

Oval, short |

smooth |

Present, short |

absent |

40-50 eggs |

short |

on larva in gall, medium dry |

| Dichatomus acerinus |

Pear, short |

smooth |

Absent |

absent |

50 |

short |

Inquiline, dry gall |

| Eupelmus microzonus |

Oval, long |

smooth |

Present, short |

present |

10 |

short |

on larva in gall, dry |

| Eurytoma brunniventris |

Elongate/Oval, short |

papillate |

Present, short |

present |

4-5 |

short |

on larva in gall, dry |

| Eurytoma infracta |

Oval, long |

papillate |

Present, long |

present |

4-10 |

short |

on larva in gall, dry |

| Eurytoma rosae |

Oval long |

papillate |

Present, short |

present |

10-12 |

long |

on larva in gall, dry |

| Eurytoma strigifrons |

Oval, long |

smooth |

Present, long |

present |

20 |

long |

on larva in gall, dry |

| Sycophila biguttata |

Oval, short |

smooth |

Present, short |

present |

6-8 |

long |

inside larva, fluid |

| Sycophila binotata |

Oval, short |

smooth |

Present, long |

present |

- |

short |

inside larva, fluid |

| Sycophila mayri |

Oval, short |

smooth |

Present, long |

present |

15-16 |

short |

inside larva, fluid |

| Sycophila submutica |

Oval, short |

smooth |

Present, short |

present |

60 |

not measured |

inside larva, fluid |

| Ormyrus nitidulus |

Elongate, long |

smooth |

Absent |

absent |

- |

long |

on larva in gall, dry |

| Ormyrus papaveris |

Elongate, long |

irregular ridges |

Absent |

absent |

15 |

long |

on larva in gall, dry |

| Ormyrus wachtli |

Elongate, long |

smooth |

Absent |

absent |

12-14 |

short |

on larva in gall, dry |

| Cecidostiba fungosa |

Elongate, short |

smooth |

Absent |

absent |

19-20 |

short |

on larva in gall, medium dry |

| Mesopolobus mediterraneus |

Oval/Sub- rectangular, short |

smooth |

Absent |

absent |

- |

short |

on larva in gall, dry |

| Pteromalus bedeguaris |

Elongate, long |

spiny |

Absent |

absent |

6 |

long |

on larva in gall, dry |

| Stinoplus lapsanae |

Elongate, long |

smooth |

Absent |

absent |

20 |

short |

on larva in gall, dry |

| Adontomerus impolitus |

Elongate, long |

papillate |

Absent |

absent |

8 |

long |

on larva in gall, dry |

| Chalcimerus borceai |

Elongate, long |

smooth |

Absent |

absent |

6 |

long |

on larva in gall, dry |

| Glyphomerus stigma |

Elongate, long |

partly spiny |

Absent |

absent |

- |

long |

on larva in gall, dry |

| Megastigmus aculeatus |

Oval, short |

smooth |

Present, long |

absent |

5-9 |

long |

Seed eater, dry |

| Torymus bedeguaris |

Elongate, n.m |

smooth |

Absent |

absent |

50-70 |

long |

on larva in gall, dry |

| Torymus nobilis |

Elongate, long |

smooth |

Absent |

absent |

10-12 |

long |

on larva in gall, dry |

| Torymus rubi |

Oval/Sub-rectangular, short |

smooth |

Absent |

absent |

- |

long |

on larva in gall, dry |

|

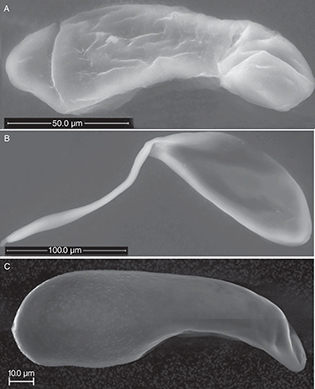

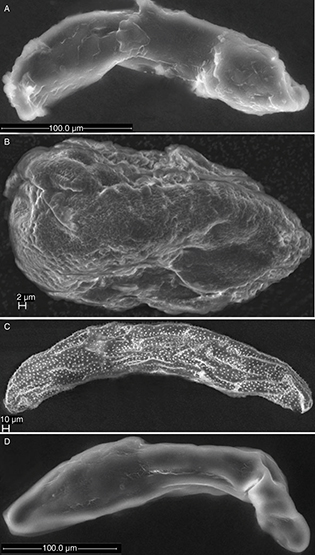

Fig. 1.— Eggs of Eulophidae A) Aprostocetus epicharmus B) Aulogymnus skianeuros and C) Dichatomus acerinus. The anterior end of the egg is to the left. Fig. 1.— Eggs of Eulophidae A) Aprostocetus epicharmus B) Aulogymnus skianeuros and C) Dichatomus acerinus. The anterior end of the egg is to the left.

Fig. 1.— Huevos de Eulophidae A) Aprostocetus epicharmus B) Aulogymnus skianeuros y C) Dichatomus acerinus. La parte anterior del huevo es la izquierda.

|

|

|

Fig. 2.— Egg of the Eupelmus microzonus (Eupelmidae). Fig. 2.— Egg of the Eupelmus microzonus (Eupelmidae).

Fig. 2.— Huevo de Eupelmus microzonus (Eupelmidae).

|

|

|

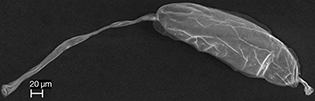

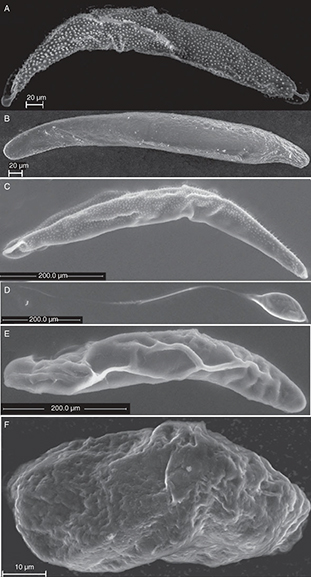

Fig. 3.— Eggs of Eurytomidae A) Eurytoma brunniventris, B) Eurytoma infracta C) Eurytoma rosae D) Eurytoma strigifrons, E) Sycophila biguttata F) Sycophila binotata G) Sycophila mayri and H) Sycophila submutica. Fig. 3.— Eggs of Eurytomidae A) Eurytoma brunniventris, B) Eurytoma infracta C) Eurytoma rosae D) Eurytoma strigifrons, E) Sycophila biguttata F) Sycophila binotata G) Sycophila mayri and H) Sycophila submutica.

Fig. 3.— Huevos de Eurytomidae A) Eurytoma brunniventris, B) Eurytoma infracta C) Eurytoma rosae D) Eurytoma strigifrons, E) Sycophila biguttata F) Sycophila binotata G) Sycophila mayri y H) Sycophila submutica.

|

|

|

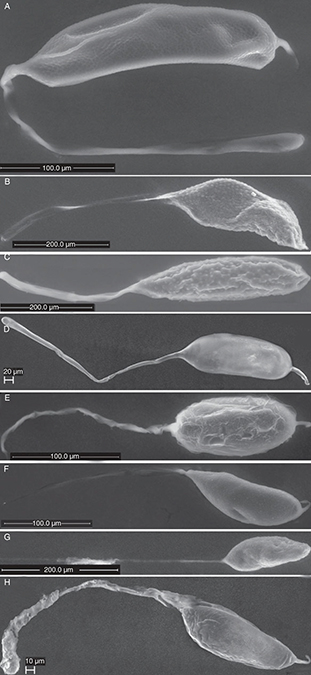

Fig. 4.— Eggs of Ormyridae A) Ormyrus nitidulus, B) Ormyrus papaveris and C) Ormyrus wachtli. Fig. 4.— Eggs of Ormyridae A) Ormyrus nitidulus, B) Ormyrus papaveris and C) Ormyrus wachtli.

Fig. 4.— Huevos de Ormyridae A) Ormyrus nitidulus, B) Ormyrus papaveris y C) Ormyrus wachtli.

|

|

|

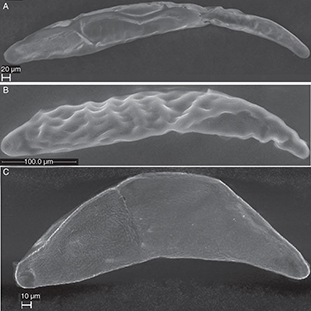

Fig. 5.— Eggs of Pteromalidae A) Cecidostiba fungosa, B) Mesopolobus mediterraneus, C) Pteromalus bedeguaris and D) Stinoplus lapsanae. Fig. 5.— Eggs of Pteromalidae A) Cecidostiba fungosa, B) Mesopolobus mediterraneus, C) Pteromalus bedeguaris and D) Stinoplus lapsanae.

Fig. 5.— Huevos de Pteromalidae A) Cecidostiba fungosa, B) Mesopolobus mediterraneus, C) Pteromalus bedeguaris y D) Stinoplus lapsanae.

|

|

|

Fig. 6.— Eggs of Torymidae. A) Adontomerus impolitus B) Chalcimerus borceai, C) Glyphomerus stigma, D) Megastigmus aculeatus, E) Torymus nobilis and F) Torymus rubi. Fig. 6.— Eggs of Torymidae. A) Adontomerus impolitus B) Chalcimerus borceai, C) Glyphomerus stigma, D) Megastigmus aculeatus, E) Torymus nobilis and F) Torymus rubi.

Fig. 6.— Huevos de Torymidae. A) Adontomerus impolitus B) Chalcimerus borceai, C) Glyphomerus stigma, D) Megastigmus aculeatus, E) Torymus nobilis y F) Torymus rubi.

|

|

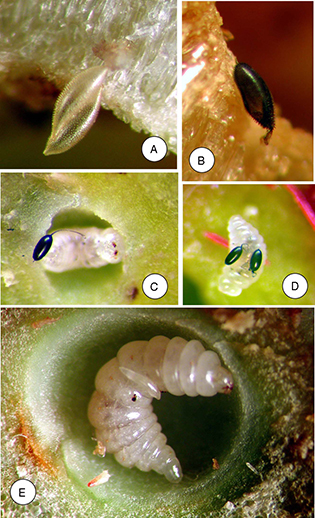

For species in our material (Fig. 11), the peduncle does not appear to be attached to the host tissue, but aiding the egg in passing through the ovipositor. The

diameter of the eggs with peduncle (mean: 60.85 μm) is narrower than the eggs without peduncle (mean: 62.15 μm) (Table 3). The eggs with a peduncle have a shorter egg body (mean: 205.66 μm) than the ones without a peduncle (mean: 353.69 μm) (Table 3). The non-pedunculate egg may be short and pear-shaped (Eulophidae), oval/subrectangular (Mesopolobus mediterraneus and Torymus rubi), but most often elongate and rather long egg body.

The ovipositor length is positively correlated with egg body length. In 75 % of the species, a short egg body is associated

with short ovipositor and long egg body with a long ovipositor (Table 4). There are 3 exceptions in which the egg body is short and the ovipositor is long (Sycophila biguttata, Megastigmus aculeata and Torymus rubi) and 3 species in which the egg body is long and the ovipositor is short (Eupelmus microzonus, Eurytoma infracta, Ormyrus wachtli) and this may in some cases be attributed to the fact that either the ovipositor or the egg body length was in the vicinity

of the limit between what we defined as short and long or perhaps, in a few cases, the eggs may not have been fully mature

when examined.

Egg body width is always wider than external ovipositor width measurements (Table 3) meaning that the egg shell must be flexible to facilitate the oviposition through the egg canal.

EULOPHIDAE

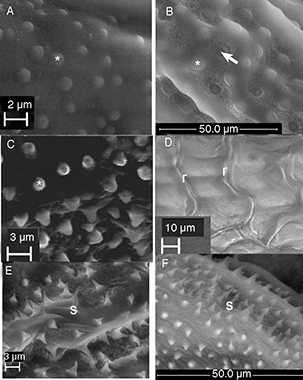

The eggs of Aprostocetus epicharmus (Walker, 1839) (Tetrastichinae) and Dichatomus acerinus (Eulophinae) are elongate and somewhat wider in the anterior end (Fig. 1A) than at the posterior end. The specimens of Dichatomus acerinus contained around 50 eggs of approximately the same size (Table 4), The surface is mostly smooth, but has tiny papillae in the anterior half in Dichatomus acerinus (Figs. 1C, 7A).

The eggs of Aulogymnus skianeuros and Aprostocetus epicharmus have a smooth surface, peduncles equal in length to the egg body (Fig. 9A).

EUPELMIDAE

The egg of Eupelmus microzonus Förster, 1860 is elongate with a peduncle that is slightly longer than the egg body at the anterior end and a short process

at the posterior end (Fig. 2). The micropyle is clearly visible at the end of the peduncle (Fig. 9B). The surface of the egg is entirely smooth.

EURYTOMIDAE

Four species each of the genera Eurytoma and Sycophila represent Eurytomidae in the present study (Table 2). Eurytoma eggs have an elongate egg body with a peduncle at one end and a short process at the other end (Figs. 3A-D). The latter is more pronounced in E. brunniventris Ratzeburg, 1852 (Fig. 3A) and E. strigifrons Thomson, 1876 (Fig. 3D) than in E. infracta Mayr, 1904 (Fig. 3B) and E. rosae (Fig. 3C). The peduncle is generally between 1 and 1 1/2 times as long as the egg body. Sometimes the eggs are of unequal size and

immature eggs can be seen inside the females.

The micropyle was observed at the end of the peduncle in E. brunniventris and E. strigifrons (Fig. 9C), but not in the other two species. Rounded papillae (* in Fig. 7ABC) and/or small depressions (white arrow Figs. 7B, 8C) (and sometimes both intermixed (Fig. 7B) can be seen on the egg body surface of E. rosae (Fig. 7B) and E. infracta (Fig. 3B) and E. brunniventris (Fig. 8C), whereas the E. strigifrons (Fig. 3D) egg surface is entirely smooth.

|

Fig. 7.— Surface of the egg A) partly covered by flat papillae (*) Dichatomus acerinus (Eulophidae), B) entirely covered by alternating papillae (*) and depressions (arrow) Eurytoma rosae (Eurytomidae), C) elevated rounded papillae (*) Adontomerus impolitus (Torymidae), D) irregular ridges (r) Ormyrus papaveris or E) sharply pointed spines (s) Pteromalus bedeguaris (Pteromalidae) and F) Glyphomerus stigma (Torymidae). Fig. 7.— Surface of the egg A) partly covered by flat papillae (*) Dichatomus acerinus (Eulophidae), B) entirely covered by alternating papillae (*) and depressions (arrow) Eurytoma rosae (Eurytomidae), C) elevated rounded papillae (*) Adontomerus impolitus (Torymidae), D) irregular ridges (r) Ormyrus papaveris or E) sharply pointed spines (s) Pteromalus bedeguaris (Pteromalidae) and F) Glyphomerus stigma (Torymidae).

Fig. 7.— Superficie del huevo A) en parte cubierta por papilas planas Dichatomus acerinus (Eulophidae), B) cubierta enteramente por papilas y depresiones alternando Eurytoma rosae (Eurytomidae), C) papilas elevadas redondeadas Adontomerus impolitus (Torymidae), D) crestas irregulares Ormyrus papaveris or E) espinas puntiagudas Pteromalus bedeguaris (Pteromalidae) y F) Glyphomerus stigma (Torymidae).

|

|

|

Fig. 8.— Change in the shape and size of the egg of the Eurytoma brunniventris (Eurytomidae) A) ovarian egg and B) post oviposition egg, C) egg surface structure of ovarian egg and D) spiny egg surface

of post-oviposition egg. Fig. 8.— Change in the shape and size of the egg of the Eurytoma brunniventris (Eurytomidae) A) ovarian egg and B) post oviposition egg, C) egg surface structure of ovarian egg and D) spiny egg surface

of post-oviposition egg.

Fig. 8.— Cambio en el tamaño y forma del huevo de Eurytoma brunniventris (Eurytomidae) A) huevo ovárico y B) huevo después de la puesta, C) estructura de la superficie del huevo avárico y D) superficie

espinosa del huevo después de la puesta.

|

|

Observations were done of post-oviposition eggs of E. brunniventris in the gall of Cynips quercus (agamic generation). What can be seen as small rounded structures in the depressions (white arrow in Fig. 8C) in the ovarian egg, apparently develop into hooks/spines (Fig. 8D) in the post-oviposition egg and the egg expands to at least double the size of the ovarian egg after being deposited in

the gall.

The eggs of Sycophila biguttata (Swederus, 1795), S. binotata (Fonscolombe, 1832), S. mayri (Erdös, 1959) and S. submutica (Thomson, 1876) (Fig. 3E-H) are very similar to each other and are oval and tapered at both ends.

They carry a long slender peduncle at one end and a shorter process at the other end. It is difficult to measure the length

of the peduncle as it is almost impossible to disentangle from the rest of the peduncles in the egg mass without breaking

and it appears to be very flexible and is easily stretched out, but it appear to be several times as long as the egg body.

The micropyle was seen at the end of the peduncle of S. submutica. The surface of the egg body is entirely without structure and appears flaky and soft.

|

Fig. 9.— Micropyle (arrows) at anterior end of egg of A) Aulogymnus skianeuros (Eulophidae) B) Eupelmus microzonus (Eupelmidae), C) Eurytoma strigifrons (Eurytomidae), D) Ormyrus papaveris and E) Ormyris wachtli (Ormyridae). Fig. 9.— Micropyle (arrows) at anterior end of egg of A) Aulogymnus skianeuros (Eulophidae) B) Eupelmus microzonus (Eupelmidae), C) Eurytoma strigifrons (Eurytomidae), D) Ormyrus papaveris and E) Ormyris wachtli (Ormyridae).

Fig. 9.— Micropilo (flechas) y extremo anterior del huevo de A) Aulogymnus skianeuros (Eulophidae) B) Eupelmus microzonus (Eupelmidae), C) Eurytoma strigifrons (Eurytomidae), D) Ormyrus papaveris y E) Ormyris wachtli (Ormyridae).

|

|

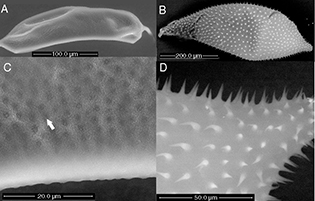

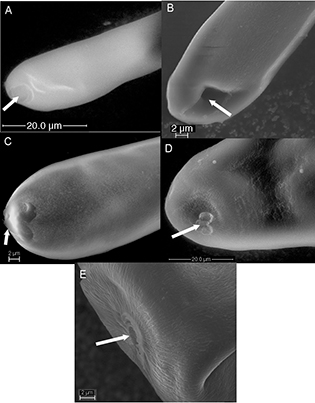

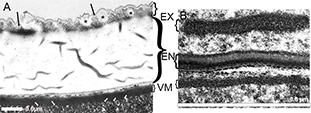

Sections were made of the eggs of S. biguttata and examined in the transmission electron microscope (Fig. 10B). The eggshell consists of an inner vitelline membrane (VM) forming a firm layer around the oocyte, and the outer chorion.

The vitelline membrane is the thinnest layer of the eggshell (about 0.03 μm in thickness) and is electron dense and uniform

in structure. The chorion is separated in the inner endochorion (EN) and the outer exochorion (EX). The endochorion is further

divided into an electron dense inner part and a more electron translucent outer part. It is slightly narrower (about 0.070

μm in thickness) than the exochorion (about 0.076 μm in thickness), which appears uniform in structure.

|

Fig. 10.— Section of the eggshell of A) the ectoparasitoid Cecidostiba fungosa (Pteromalidae), (the stars (*) mark vesicle-like structures and black arrows mark crystalline structures in the exochorion,

the white arrows mark the extension that anchor the vitelline membrane into the oocyte) and of B) the endoparasitoid Sycophila biguttata (Eurytomidae) VM= vitelline membrane, EN= endochorion, EX=exochorion. Fig. 10.— Section of the eggshell of A) the ectoparasitoid Cecidostiba fungosa (Pteromalidae), (the stars (*) mark vesicle-like structures and black arrows mark crystalline structures in the exochorion,

the white arrows mark the extension that anchor the vitelline membrane into the oocyte) and of B) the endoparasitoid Sycophila biguttata (Eurytomidae) VM= vitelline membrane, EN= endochorion, EX=exochorion.

Fig. 10.— Sección de la cáscara del huevo de A) el ectoparasitoide Cecidostiba fungosa (Pteromalidae), (el asterisco(*) indica estructuras en forma de vesícula, la flecha negra apunta a estructuras cristalinas

en el exocorion y la flecha blanca marca la extensión que ancla la membrana vitelina en el oocito) y de B) el endoparasitoide

Sycophila biguttata (Eurytomidae) VM= membrana vitelina, EN= endocorion, EX=exocorion.

|

|

ORMYRIDAE

The eggs of Ormyrus (Fig. 4) are highly elongate and slightly broader in the anterior end than in the posterior end. Neither of the 3 examined species

have peduncles. The micropyle was seen as quite a large 2 or 3-lobed opening at the anterior end of the eggs of O. wachtli Mayr, 1904 (Fig. 4C) and O. papaveris (Perris, 1840) (Fig. 4B). The surface appears more or less smooth, but in O. papaveris several of the examined species have eggs with irregular ridges on the surface, which appears as a grid pattern (marked by

r in Fig. 7D).

PTEROMALIDAE

The examined eggs of Pteromalidae are elongate and tapered at both ends as in Pteromalus bedeguaris (Linnaeus, 1758) (Fig. 5C) or somewhat broader in the anterior end as in Stinoplus lapsanae Graham, 1969 (Fig. 5D) and Cecidostiba fungosa (Geoffoy, 1785) (Fig. 5A). None of the studied species have pedunculated eggs.

The micropyle was not observed in any of the pteromalid eggs. The surface of the egg is smooth in all the species except Pteromalus bedeguaris, in which it is covered in small spine-like structures (marked by s in Fig. 7E).

The eggshell of Cecidostiba fungosa was examined using TEM (Fig. 10A). It consists of an inner electron dense vitelline membrane (about 0.3 μm in thickness), a middle endochorion (about 2 μm

in thickness) and an outer relatively thin electron dense exochorion (about 0.4 μm in thickness). The exochorion may contain

vesicle-like structures (marked by * on Fig. 10A) as well as crystalline structures (black arrows on Fig. 10A), whereas the endochorion is uniform and apparently gelatinous in structure. The innermost layer, the vitelline membrane

is electron dense and appears to be anchored by extensions (white arrows on Fig. 10A) into the oocyte.

TORYMIDAE

The shape of the examined torymid eggs varies from elongate and slightly broader at the anterior end in Adontomerus impolitus (Askew & Nieves-Aldrey, 1988) (Fig. 6A), Chalcimerus borceai Steffan & Andriescu, 1962 (Fig. 6B), Glyphomerus stigma (Fabricius, 1793) (Fig. 6C) and Torymus nobilis Boheman, 1834 (Fig. 6E) to short and subrectangular as in Torymus rubi (Schrank, 1781) (Fig. 6F) or oval with a long peduncle at the posterior end and a short process at the posterior end as in Megastigmus aculeatus (Fig. 6D).

The micropyle was not observed for any of these species. The egg surface is smooth in all the examined torymid species except

in Adontomerus impolitus (Fig. 7C) in which the entire surface is covered in papilla-like structure and in Glyphomerus stigma (marked by * in Fig. 7F) in which at least parts of the egg are covered with small spines.

DiscussionTOP

EXTERNAL EGG FEATURES

Several functions have been suggested and shown for the peduncle of eggs of parasitic wasps. Fulton (1933) described the oviposition procedure for Pteromalus (as Habrocytus) cerealellae and explained how the egg body, which was 0,14-0,16 mm in diameter distributed its content along the whole length of the peduncle when the egg body enters the egg canal which has a diameter of only 0,04 mm. In other groups, such as Exenterus (Hymenoptera: Ichneumonidae), the peduncle varies from a simple stalk with a knob-like anchor to a highly specialized double stalk. The former simply attaches the eggs to the host larva’s integument, whereas the latter is firmly inserted into the host larva’s cuticle, which makes these eggs much less sensitive to desiccation than the former (Mason, 1967). In the eggs of the eucharitid Golumiella longipetiolata, the typical eucharitid peduncle is absent and a posterior anchor attach the egg to the leaf petiole where the eggs are deposited

vertically onto the surface (Heraty et al., 2004). At the apical end a pseudostalk covered with secretion, which is believed to attract ants that act as host for the larvae

of this species.

Respiration is a documented function of the peduncle in some groups of wasps. In several encyrtid species the egg has been

shown to leave a portion of its peduncle on the outside of the host larva, so the encyrtid larva has access to oxygen when

it hatches (Maple, 1947). Similarly, for Eurytoma amygdali (Hymenoptera: Eurytomidae) a respiratory function was suggested for the tip of the peduncle as this part of the egg apparently

remained on the outside of the almond fruit after oviposition (Mouzaki & Margaritis, 1994).

|

Fig. 11.— Color plate of eggs deposited inside cynipid galls A-B) Eurytoma brunniventris (Eurytomidae) egg inside gall of Cynips quercus, C-D) Eurytoma rosae (Eurytomidae) eggs on larva of the inquiline Periclistus brandtii in a Diplolepis mayri gall, E) egg of Pteromalus bedeguaris (Pteromalidae) on Diplolepis mayri larva. Fig. 11.— Color plate of eggs deposited inside cynipid galls A-B) Eurytoma brunniventris (Eurytomidae) egg inside gall of Cynips quercus, C-D) Eurytoma rosae (Eurytomidae) eggs on larva of the inquiline Periclistus brandtii in a Diplolepis mayri gall, E) egg of Pteromalus bedeguaris (Pteromalidae) on Diplolepis mayri larva.

Fig. 11.— Lámina en color de huevos depositados en el interior de agallas de cinípidos A-B) Eurytoma brunniventris (Eurytomidae) huevo dentro de la agalla de Cynips quercus, C-D) Eurytoma rosae (Eurytomidae) huevos sobre larvas del inquilino Periclistus brandtii en una agalla de Diplolepis mayri, E) huevo de Pteromalus bedeguaris (Pteromalidae) sobre una larva de Diplolepis mayri.

|

|

Pedunculate eggs are found in most chalcid families (Fig. 12) in species ovipositing both inside host larvae in a fluid environment as well as in the drier environment on the host larvae

inside galls on different plants (Table 4), so pedunculate egg are apparently not restricted to certain oviposition habits.

|

Fig. 12.— Phylogenetic tree modified from the combined implied weight tree in Heraty et al. (2013) with egg drawings or SEM micrographs representing egg shapes in families with described eggs. Redrawings were made for representatives of families not examined here (Silvestri, 1916; Parker, 1924a; Grandi, 1929; Dowden, 1935; Cendaña, 1937; Clausen, 1940; Jackson, 1961; La Salle & LeBeck, 1983; Noyes, 1990a; Rosen et al., 1992). Fig. 12.— Phylogenetic tree modified from the combined implied weight tree in Heraty et al. (2013) with egg drawings or SEM micrographs representing egg shapes in families with described eggs. Redrawings were made for representatives of families not examined here (Silvestri, 1916; Parker, 1924a; Grandi, 1929; Dowden, 1935; Cendaña, 1937; Clausen, 1940; Jackson, 1961; La Salle & LeBeck, 1983; Noyes, 1990a; Rosen et al., 1992).

Fig. 12.— Árbol filogenético dibujado a partir del árbol combinado de pesaje implícito en Heraty et al. (2013) con dibujos del huevo o SEM microfotografías representando formas de huevos de familias con huevos descritos. Se redibujaron

los huevos de representantes de familias que no fueron examinadas en este trabajo (Silvestri, 1916; Parker, 1924a; Grandi, 1929; Dowden, 1935; Cendaña, 1937; Clausen, 1940; Jackson, 1961; La Salle & LeBeck, 1983; Noyes, 1990a; Rosen et al., 1992).

|

|

The sperm entrance or micropyle is usually at the anterior end of the eggs for most parasitic wasps including Chalcidoidea

(Rotheram, 1973) or at the tip of the peduncle when present (Maple, 1947; Wishart & Monteith, 1954).

In eggs of at least some species of Eurytomidae that carry a long peduncle at the anterior end as well as a shorter process

at the posterior pole, the micropyle has been reported at the end of the egg that carries the short posterior process (Claridge & Askew, 1960; Mouzaki & Margaritis, 1994; Zarani & Margaritis, 1994). We found, however, an opening at the tip of the long anterior peduncle of both Eurytoma brunniventris and Eurytoma strigifrons (Hymenoptera: Eurytomidae) and assume that this structure is equivalent with the micropyle of the other chalcidoidoid eggs

with peduncle.

EGG LOAD

The approximate egg number varies considerably (Table 4). The size of the egg load may be indicative of whether the species is pro-ovigenic (female emerging with a full complement

of mature eggs) or synovigenic (maturing eggs continuously). Compared with many other koinobiont parasitoid wasps and oak

gall wasps that are considered pro-ovigenic and carry hundreds or more than a thousand ovarian eggs (Quicke, 1997; Vårdal et al., 2003), our result show a generally relatively low egg count, which may be an indication of synovigeny in some species (Table 4).

EGG SURFACE

Papillae or hook-like structures, spines and ridges are on the surface of eggs of some ectoparasitoid species (Fig. 7, Table 4). These structures may help to attach the egg to the host larva or the substrate where it is deposited, (Claridge & Askew, 1960; Arthur, 1961; Quicke, 1997). No surface structures were observed in eggs of endoparasitoids like Aprostocetus (Eulophidae) and Sycophila (Eurytomidae). All the studied endoparasitoids have a smooth chorion (Table 4), and this appears to be the most common state for eggs that are deposited inside another insect (Parker, 1924a; Hagen, 1964).

The surface structure of the mymarid egg is smooth, and this is also the case for the eggs of other outgroup taxa like Scelionidae and Diapriidae (Clausen, 1940) (Fig. 12; Tables 1, 4). This appears to be the most common state for egg surface throughout the superfamily. Surface structures like spines and

papillae possibly evolved independently in Eurytomidae, Leucospidae, Torymidae and Pteromalidae and in Ormyridae. The eggshell

of some Perilampidae, Trichogrammatidae, Eurytomidae, Encyrtidae and Ormyridae are heavily sculptured with irregular ridges

(Table 1, Fig. 12). All the species, for which these surface structures are observed, are ectoparasitoids.

The surface sculpture of the ovarian and oviposited egg is different in Eurytoma brunniventris. In the ovarian egg, the surface is covered by depressions (Fig. 8C). In the depressions small projections with blunt tips can be seen in the ovarian egg, that apparently extend into spines or hooks in the post-oviposition egg (Fig. 8D). Claridge & Askew (1960) also observed that the spines were not present in the ovarian egg of Eurytoma brunniventris (Hymenoptera: Eurytomidae). Development of spines after oviposition appears to be a good strategy as they would probably

delay the passage of the egg through the narrow egg canal, yet several species have ovarian eggs with well-developed spines

(Fig. 7E-F). King et al. (1968) observed that the spines of Catolaccus sp. (Pteromalidae) are an integral part of the flexible translucent layer (endochorion) and protrude through the exochorion.

Presumably the flexibility of the endochorion will allow the spines to fold when passing through the egg canal.

The egg surface in Ormyrus papaveris has irregular ridges (Fig. 2D). In several insect orders similar patterns are believed to be caused by imprints of the follicle cells that have participated

in eggshell formation (Hinton, 1981).

THE EGGSHELL

Endoparasitoids often have hydropic eggshells, which have the ability to take up substances through the chorion (Quicke, 1997). To facilitate this action as well as the swelling of the egg after nutrion-uptake, the eggshell is often highly convoluted

and flexible and thinner than the eggshell of anhydropic eggs, which contains all the yolk necessary for the embryo development

(Quicke, 1997). A thicker impermeable anhydropic eggshell as well as enough yolk to nurture the embryo during the entire egg stage is expected

for species exposing their eggs to desiccation (Quicke, 1997). Depending of the environment of the host larva, this may be the case for several ectoparasitic species, which may thus

be expected to have thicker eggshells than endoparasitoids into which the eggs are normally deposited directly into the body

tissue of the host. The egg of the ectoparasitic Cecidostiba fungosa has a thick chorion (2.5 μm) in which the endochorion is about 4 times as thick as the exochorion (Fig. 10A). In the endoparasitic Sycophila biguttata (Fig. 10B) the endochorion is as thick as the exochorion and 15 times thicker than in Cecidostiba fungosa (0.15 μm). In the examined material it is clear that the eggs of the endoparasitoids are narrower (mean: 44.1 μm) and shorter

(mean: 136.5 μm) than the eggs of the ectoparasitoids (width mean: 65.2 μm, length mean: 345.25 μm) (Tables 2, 3) and one reason for this is probably that in our material the female ectoparasitoids in most cases are much larger the female

endoparasitoids.

ConclusionsTOP

The chalcidoid egg is extremely variable in size, shape and surface structure. Certain families like polyphyletic Pteromalidae

and monophyletic Torymidae exhibit all of the egg types, whereas only one egg type with relatively little variation is observed

in certain families like Eurytomidae, Ormyridae, Perilampidae and Eucharitidae. In general, eggs of endoparasitoids have unsculptured

eggshell, whereas ectoparasitoid often have egg surface structure, which might be involved in the attachment of the egg on

the cuticle of the host.

The perception that the endoparasitoid eggshell (endochorion) is thin, whereas the ectoparasitoid eggshell (endochorion) is

several times thicker is supported by our results.

AcknowledgmentsTOP

We are greatly indebted to the European Union´s Programme Structuring the European Research Area under SYNTHESYS for financing

a visit for the senior author to the Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales (MNCN) in Madrid. We are grateful to Josefina Cabarga

for administrating the SYNTHESYS visit. JLN-A was supported by projects CGL2009-10111 and CGL-2010-15786 of the Spanish PLAN

NACIONAL DE I+D+i.

Gary Wife and Stefan Gunnarsson at the Biological Structural Analysis facility at Evolutionary Biology Centre at Uppsala University,

Sweden and Laura Tormo at the electron microscope facility at MNCN, Madrid helped with the scanning electron microscope. Carina

Svensson and Lena Gustavsson at the Department of Zoology at the Swedish Museum of Natural History in Stockholm, Sweden helped

us prepare the egg sections and use the transmission electron microscope. We thank Carlo Polidori who critically reviewed

and made useful comments on the manuscript. Johan Nylander (Bioinformatics Infrastructure for Life Sciences (BILS) and Swedish

Museum of Natural History) is also acknowledged for technical support.

ReferencesTOP

| ○ |

Arthur, A. P., 1961. The cleptoparasitic habits and the immature stages of Eurytoma pini Bugbee (Hym: Chal) a parasite of the European pine shoot moth, Rhyacionia buolinana (Schiff.) (Lep. Olethreutidae). The Canadian Entomologist, 93: 655-660. http://dx.doi.org/10.4039/Ent93655-8 |

| ○ |

Askew, R. R., 1961. On the biology of oak galls of Cynipidae (Hymenoptera in Britain). Transactions of the Society of British Entomology, 14: 237-268.

|

| ○ |

Askew, R. R., 1966. Observations on the British species of Megastigmus Dalman (Hym. Torymidae) which inhabit cynipid oak galls. Entomologist, 99: 124-128.

|

| ○ |

Askew, R. R., Melika, G., Pujade-Villar, J., Schönrogge, K., Stone, G. N. & Nieves-Aldrey, J. L., 2013. Catalogue of parasitoids

and inquilines in cynipid oak galls in the West Palaearctic. Zootaxa, 3643: 1-133. http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3643.1.1 |

| ○ |

Askew, R. R., Plantard, O, Gómez, J. F., Hernández Nieves, M. & Nieves-Aldrey, J. L., 2006. Catalogue of parasitoids in galls

of Aylacini, Diplolepidini and Pediaspidini (Cynipidae) in the West Palaearctic. Zootaxa, 1301: 1-60.

|

| ○ |

Bailey, R., Schönrogge, K., Cook, J. M., Melika, G., Csóka, G., Thúroczy, C. & Stone, G. N., 2009. Host niches and defensive

extended phenotypes structure parasitoid wasp communities. PLoS Biology, 7(8): e1000179. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1000179 |

| ○ |

Bakkendorf, O., 1934. Biological investigations on some Danish hymenopterous egg-parasites, especially in homopterous and

heteropterous eggs, with taxonomic remarks and descriptions of new species. Entomologiske Meddelelser, 19: 1-135.

|

| ○ |

Beament, J. W. L., 1946. The waterproofing process in the eggs of Rhodnius prolixus Stahl. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences, 88: 407-418. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspb.1946.0021 |

| ○ |

Cameron, E., 1939. The holly leaf-miner (Phytomyza ilicis, Curt.) and its parasites. Bulletin of Entomological Research, 30: 173-208.

|

| ○ |

Cendaña, S. M., 1937. Studies on the biology of Coccophagus (Hymenoptera) a genus parasitic on nondiaspine Coccidae. University of California Publications in Entomology, 6: 337-399.

|

| ○ |

Clancy, D. W., 1946. The insect parasites of Chrysopidae (Neuroptera). University of California Publications in Entomolology, 7: 403-496.

|

| ○ |

Claridge, M. F. & Askew, R. R., 1960. Sibling species in the Eurytoma rosae group (Hym., Eurytomidae). Entomophaga, 5: 141-153.

|

| ○ |

Clausen, C. P., 1940. Entomophagous Insects. McGraw-Hill. New York. 688 pp.

|

| ○ |

Compere, H. & Smith, H. S., 1932. The Control of the Citrophilus mealy bug, Pseudococcus gahani by Australian parasites. Hilgardia, 6: 585-6l7.

|

| ○ |

Dowden, P. B., 1935. Brachymeria intermedia (Nees), a primary parasite, and B. compsilurae (Cwfd.), a secondary parasite, of gypsy moth. Journal of Agricultural Research, 50: 495-523.

|

| ○ |

Fabré, J. H., 1886. Souvenirs entomologiques (Troisième Série) études sur l’instinct et les moeurs des insectes. Troisième

Edition. Librairie Ch. Delagrave. Paris. 433 pp.

|

| ○ |

Fisher, J. P., 1965. A contribution to the biology of Eurytoma curculionum Mayr (Hym., Eurytomidae). Entomophaga, 10: 317-318.

|

| ○ |

Fulton, B. B., 1933. Notes on Habrocytus cerealellae, parasite of the agoumois grain moth. Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 26: 536-553.

|

| ○ |

Gibson, G. A. P., 1993. Superfamilies Mymarommatoidea and Chalcidoidea. In: Goulet, H. & Huber, J. T. (Eds.). Hymenoptera of the world: An identification guide to families. Research Branch (Agriculture Canada). Ottawa: 570-655.

|

| ○ |

Gómez, J. F. & Nieves-Aldrey, J. L., 2012. Notes on the larval morphology of Pteromalidae (Hymenoptera: Chalcidoidea) species

parasitoids of gall wasps (Hymenoptera: Cynipidae) in Europe. Zootaxa, 3189: 39-55.

|

| ○ |

Gómez, J. F., Nieves-Aldrey, J. L. & Hernández Nieves, M., 2008. Comparative morphology, biology and phylogeny of terminal-instar

larvae of the European species of Toryminae (Hym., Chalcidoidea, Torymidae) parasitoids of gall wasps (Hym. Cynipidae). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 154: 676–721. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.2008.00423.x |

| ○ |

Gómez, J. F., Nieves-Aldrey, J. L., Hernández Nieves, M. & Stone, G. N., 2011. Comparative morphology and biology of terminal

instar larvae of some Eurytoma (Hymenoptera, Eurytomidae) species parasitoids of gall wasps (Hymenoptera, Cynipidae) in western Europe. Zoosystema, 33(3): 287–323.

|

| ○ |

Gómez, J. F., Nieves-Aldrey, J. L. & Stone, G. N., 2013. On the morphology and biology of the terminal-instar larvae of some

european species of Sycophila (Hymenoptera, Eurytomidae) parasitoids of gall wasps (Hymenoptera, Cynipidae). Journal of Natural History, 47(47-48): 2937-2960. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00222933.2013.791937 |

| ○ |

Gordh, G., Grissell, E. E. & Burks, B. D., 1979. Superfamily Chalcidoidea. In: Krombein, K. V., Hurd, P. D., Smith, D. R.

& Burks, B. D. (Eds.). Catalog of Hymenoptera in America North of Mexico. Vol. 1. Smithsonian Institution Press. Washington DC: 743-1043.

|

| ○ |

Grandi, G., 1929. Studio morfologico e biologico della Blastophaga psenes (L.). 2a edizizione riveduta. Bollettino del Laboratorio

di Entomologia del R. Istituto Superiore Agrario di Bologna, 2: 1-147.

|

| ○ |

Hagen, K. S., 1964. Developmental Stages of Parasites. In: Debach, P. (Ed.). Biological control of Insect Pests and Weeds. Chapman & Hall. London: 168-246.

|

| ○ |

Heraty, J. M., Burks, B. D., Cruaud, A., Gibson, G., Liljeblad, J., Munro, J., Rasplus, J.-Y., Delvare, G., Janšta, P., Gumovsky,

A. V., Huber, J. T., Woolley, J. B., Krogmann, L., Heydon, S., Polaszek, A., Schmidt, S., Darling, D. C., Gates, M. W., Mottern,

J. L., Murray, E., Dal Molin, A., Triapitsyn, S., Baur, H., Pinto, J. D., Van Noort, S., George, J. & Yoder, M., 2013. A Phylogenetic

Analysis of the Megadiverse Chalcidoidea (Hymenoptera). Cladistics, 29(5): 466-542. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/cla.12006 |

| ○ |

Heraty, J. M. & Darling, D. C., 1984. Comparative morphology of the planidial larvae of Eucharitidae and Perilampidae (Chalcidoidea).

Systematic Entomology, 9: 309-328. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3113.1984.tb00056.x |

| ○ |

Heraty, J. M., Hawks, D., Kostecki, J. S. & Carmichael, A., 2004. Phylogeny and behaviour of the Golumiellinae, a new subfamily

of the ant-parasitic Eucharitidae (Hymenoptera: Chalcidoidea). Systematic Entomology, 29: 544-559.

|

| ○ |

Hinton, H. E., 1981. Biology of Insect Eggs. Pergamon Press. Oxford. 1125 pp.

|

| ○ |

Iwata, K., 1962. The comparative anatomy of the ovary in Hymenoptera. Part VI. Chalcidoidea with descriptions of the ovarian

eggs. Acta Hymenopterologica (Tokyo), 1: 383-391.

|

| ○ |

Jackson D. J., 1961. Observations on the biology of Caraphractus cinctus Walker (Hymenoptera: Mymaridae), a parasitoid of the eggs of Dytsicidae (Coleoptera). 2. Immature stages and seasonal history

with a review of mymarid larvae. Parasitology, 51: 269-294. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0031182000070530 |

| ○ |

King, P. E., 1962. Structure of the micropyle of eggs of Nasonia vitripennis. Nature, 195: 829-830. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/195829a0 |

| ○ |

King, P. E., Richards, J. G. & Copland, M. J. W., 1968. The structure of the chorion and its possible significance during

oviposition in Nasonia vitripennis (Walker) (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae) and other Chalcids. Proceedings of the Royal Entomological Society of London. Series A, General Entomology, 43: 13-20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3032.1968.tb01226.x |

| ○ |

La Salle, J., 2005. Biology of gall inducers and evolution of gall induction in Chalcidoidea (Hymenoptera): Eulophidae, Eurytomidae,

Pteromalidae, Tanaostigmatidae, Torymidae). In: Raman, A., Schaeffer, C. W. & Withers, T. M. (Eds.) Biology, Ecology and evolution of Gall-inducing Arthropods. Science Publishers. Enfield: 503-533.

|

| ○ |

La Salle, J. & LeBeck, L. M., 1983. The occurrence of encyrtiform eggs in the Tanaostigmatidae (Hymenoptera: Chalcidoidea).

Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington, 85: 397-398

|

| ○ |

Margaritis, L. H., 1985. Structure and Physiology of the Eggshell. In: Kerkut, G. A. & Gilbert, L. I. (Eds.). Comprehensive insect physiology biochemistry and pharmacology. Vol 1. Pergamon Press. Oxford: 153-230.

|

| ○ |

Mason, W. R. M., 1967. Specializations in the egg structure of Exenterus (Hymenoptera: Ichneumonidae) in relation to distribution and abundance. The Canadian Entomologist, 99: 375-384. http://dx.doi.org/10.4039/Ent99375-4 |

| ○ |

Maple, J. D., 1947. The eggs and first instar larvae of Encyrtidae and their morphological adaptations for respiration. University of California Publications in Entomology, 8: 25-117.

|

| ○ |

Mouzaki, D. G. & Margaritis, L. H., 1994. The eggshell of the almond wasp Eurytoma amygdali (Hymenoptera, Eurytomidae)-1. Morphogenesis and fine structure of the eggshell layers. Tissue and Cell, 26: 559-568. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0040-8166(94)90008-6 |

| ○ |

Muesebeck, C. F. W., 1931. Monodontomerus aereus Walker, both a primary and a secondary parasite of the brown-tail moth and the gypsy moth. Journal of Agricultural Research, 43: 445-459.

|

| ○ |

Nieves-Aldrey, J. L., 2001. Hymenoptera, Cynipidae. In: Ramos, M. A. et al. (Eds.). Fauna Ibérica, vol. XVI. Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales (CSIC). Madrid. 636 pp.

|

| ○ |

Nieves-Aldrey, J. L., Hernández Nieves, M. & Gómez, J.F., 2008. Larval morphology and biology of three European species of Megastigmus (Hymenoptera, Torymidae, Megastigminae) parasitoids of gall wasps, including a comparison with the larvae of two seed-infesting species. Zootaxa, 1746: 46-60. |

| ○ |

Noyes, J. S., 1978. On the numbers of genera and species of Chalcidoidea (Hymenoptera) in the World. Entomologist’s Gazette, 29: 163-164.

|

| ○ |

Noyes, J. S., 1990a. The number of described chalcidoid taxa in the world that are currently regarded as valid. Chalcid Forum, 13: 9-10.

|

| ○ |

Noyes, J. S., 1990b. Chapter 2.4.2. Encyrtidae. In: Rosen, D. (Ed.). The Armored Scale Insects. Their Biology, Natural Enemies and Control. Serie World Crop Pests 4B. Elsevier. Amsterdam, London, New York and Tokyo: 133-166.

|

| ○ |

Noyes, J. S., 2002. A review of the hosts and biologies of Chalcidoidea. Chalcid Forum, 24: 8-16.

|

| ○ |

Parker, H. L., 1924a. Recherches sur les forms post-embryonnaires des Chalcidiens. Annales de la Société entomologique de France, 93: 261-379.

|

| ○ |

Parker, H. L., 1924b. Contribution à la connaisssance de Chalcis fonscolombei Dufour (Hymen.). Bulletin de la Société Entomologique de France, 18: 238-240.

|

| ○ |

Phillips, W. J. & Poos, F. W., 1921. Life-history studies of three jointworm parasites. Journal of Agricultural Research, 21:405-426.

|

| ○ |

Quicke, D. L. J., 1997. Parasitic wasps. Chapman & Hall. London. 470 pp.

|

| ○ |

Richards, J. G., 1969. The structure and formation of the egg membranes in Nasonia vitripennis (Walker) (Hymenoptera, Pteromalidae). Journal of Microscopy, 89: 43-53. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2818.1969.tb00648.x |

| ○ |

Ronquist, F., Nieves-Aldrey, J. L., Buffington, M., Liu, Z., Liljeblad, J. & Nylander, J. A. A., 2015. Phylogeny, Evolution, and Classification of Gall Wasps: The Plot Thickens. PLoS ONE, 10(5): e0123301. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0123301 |

| ○ |

Rosen, D., Argov, Y. & Woolley, J. B., 1992. Biological and taxonomic studies of Chartocerus subaeneus (Hymenoptera: Signiphoridae), a hyperparasite of mealybugs. Journal of Hymenoptera Research, 1:241-253.

|

| ○ |

Rotheram, S., 1973. The surface of the egg of a parasitic insect. 1. The surface of the egg and first-instar larva of Nemeritis. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences, 183: 179-194. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspb.1973.0012 |

| ○ |

Schönrogge, K., Stone, G. N. & Crawley, M. J., 1995. Spatial and temporal variation in guild structure: parasitoids and inquilines

of Andricus quercuscalicis (Hymenoptera: Cynipidae) in its native and alien ranges. Oikos, 72: 51-60. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3546037 |

| ○ |

Schönrogge, K., Stone, G. N. & Crawley, M. J., 1996. Alien herbivores and native parasitoids: rapid developments and structure

of the parasitoid and inquiline complex in an invading gall wasp Andricus quercuscalicis (Hymenoptera: Cynipidae). Ecological Entomology, 21: 71-80. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2311.1996.tb00268.x |

| ○ |

Silvestri, F., 1916. Contribuzione all conoscenza del genre Poropoea Förster (Hymenoptera, Chalcididae). Bollettino del Laboratorio

di Zoologia Generale e Agraria della R. Scuola Superiore d’Agricoltura, Portici, 11: 120-135.

|

| ○ |

Smith, H. S., 1917. The habit of leaf-oviposition among the parasitic Hymenoptera. Psyche (Cambridge), 24: 63-68. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/1917/52524 |

| ○ |

Stefanini, M., De Martino, C. & Zamboni, L., 1967. Fixation of ejaculated spermatozoa for Electron Microscopy. Nature, 216: 713-714. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/216173a0 |

| ○ |

Vårdal, H., Sahlén, G. & Ronquist, F., 2003. Morphology and evolution of the cynipoid egg (Hymenoptera). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 139: 247-260. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1096-3642.2003.00071.x |

| ○ |

Wishart, G. & Monteith, E., 1954. Trybliographa rapae (Hymenoptera, Cynipidae), a parasite of Hylemya spp. (Diptera, Anthomyiidae). The Canadian Entomologist, 86(4): 145-154. http://dx.doi.org/10.4039/Ent86145-4 |

| ○ |

Zarani, F. E. & Margaritis, L. H., 1994. The eggshells of the almond wasp Eurytoma amygdali (Hymenoptera, Eurytomidae)., 2- The micropylar appendage. Tissue and Cell, 26: 569-577. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0040-8166(94)90009-4 |

Fig. 1.— Eggs of Eulophidae A) Aprostocetus epicharmus B) Aulogymnus skianeuros and C) Dichatomus acerinus. The anterior end of the egg is to the left.